RobertSchneiker.com

The Sphinx head is too small for the body. That

fact is obvious to anyone who sees the enormous

artwork. It just does not look right. The

proportions are wrong. One can only stare and

wonder “What was the artist thinking?”

In August 1976 I was part of a team painting a

mural on the Marc Plaza hotel parking structure in

downtown Milwaukee. Nearly a block long and

over four stories tall, this artwork approaches the

scale of the Sphinx in Egypt. I was a hired hand

working for food and beer. The artist was Sachio

Yamashita from Japan. He told me he came to the

United States as a reporter to cover the 1968

Democratic Convention in Chicago, Illinois. Then,

like now, the United States was a divided country.

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, the presumptive

Democratic candidate had been assassinated two

months prior in June, as had Martin Luther King Jr.

that April. Meanwhile, outside the convention hall

protests to end the war in Vietnam turned violent.

As an outsider, Sachio had difficulty understanding

what was going on.

In addition to being a political reporter and artist, Sachio was a restaurant reporter and a beer connoisseur. As a foodie, he felt

he could not really understand the people of the United States until he tasted their beer. Everyone told him the beer comes

from Milwaukee, so he headed north. He believed he was about to visit one of the coolest places on Earth: a city named the

Milky Way as in the galaxy, that also brews beer! The misunderstanding was Sachio’s own doing as he had mistakenly translated

Milwaukee to Japanese as “Milky Way”. Perhaps it had something to do with Wisconsin being the Dairy State.

It was in Wisconsin that Sachio learned about Native American effigy mounds. Wisconsin has the highest concentration of effigy

mounds anywhere in the world. Between about 600–1100 CE, some 15,000–20,000 effigy mounds were constructed in Southern

Wisconsin. Effigy mounds were constructed in the form of animals and ancestral spirit beings of importance to the Native

Americans. It is thought the mounds principally functioned as spiritual or religious sites, although some have served as burial

sites.

It was in Wisconsin that the Mound Builders, as they are known, built the only intaglios to be found anywhere in the World.

Intaglios are depressions in the ground sculptured in the shape of animals and spirits, making them the exact opposite of an

effigy mound. The only known remaining intaglio is in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin. Occasionally after a heavy downpour the

depression fills with water, bringing the water spirit to life.

The Mound Builders mark the transition from hunter-

gatherers to agriculture. Although maize had long been

cultivated in Central and South America, farming did

not reach the Upper Midwest until much later. Perhaps

not surprisingly, the switch to agriculture roughly

coincides with a global warming event known as the

Medieval Warm Period from 900–1300 CE. You can learn

more about the effigy mounds and intaglios at this

presentation by Robert Birmingham a former Wisconsin

state archaeologist.

The mural we were painting was Sachio’s

interpretation of a thunderbird effigy mound modified

to fit the proportions of the parking structure. To Native Americans, thunderbirds are symbols of great power and strength. They

offer protection from evil spirits. Perhaps I am biased, but I see the influence of effigy mounds in much of Sachio’s work,

including perhaps his most famous mural “Balance of Power” in Chicago. It can be seen briefly in the famous car chase in the

Blues Brothers movie. A brief profile of Sachio and his work can be seen in this episode of Chicago Tonight.

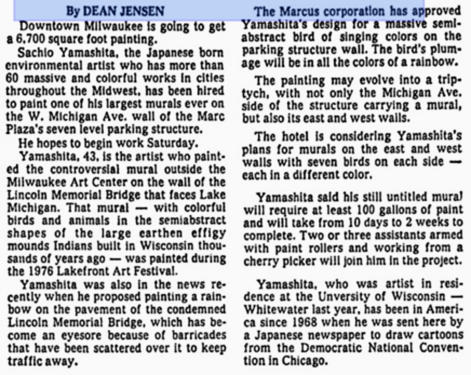

Sachio worked from a drawing to create the mural. The

drawing had to account for the horizontal parking floors

and vertical slats. The background was painted a solid

color, while the thunderbird itself was colored with

Sachio’s signature rainbow stripe motif. A bringing

together of the old and the new.

The drawing served a dual purpose. Sachio used the

drawing to sell the project to the hotel management.

This gave the decision makers an opportunity to see what

the finished mural would look like. Next using the lift

Sachio transferred the drawing to the parking structure,

using the vertical slats and parking floors as a guide.

I was one of four volunteers. In groups of two, we took

turns painting. One person used a paint roller while the

other operated the lift. Sachio directed the activities

from below. I once saved the day by repairing a leak in

the lift hydraulic line. We were on a tight schedule and

did not have time to wait for a mechanic from the lift

rental company to make the repair. Besides, I saw it

was an easy fix using the available tools.

Soon the work became routine. We would paint all day,

stopping for a quick lunch. At night we dined on hotel

food served from one of the finest restaurants in

Milwaukee, drinking imported German beer at the

hotel bar until late into the night. All costs were

covered by the hotel. We returned the next morning to

repeat the process.

With perfect summer weather, we were ahead of schedule as we began our final day of painting. Working from left to right and

bottom up, we have painted everything but the head. Sachio joined me in the bucket to outline the final section. Using the lift

controls, I raised us, but we stop short. I tried repositioning the lift, yet still we could not reach high enough to draw the head. I

got a sinking feeling, as I wonder if my repair was to blame. No, it turned out the lift was just too small.

Sachio had measured the height of the parking structure. His measurements were used to determine how large a lift was

required to paint the mural. Unfortunately, he had forgotten to account for the slope of the land.

Working from left to right no one realize the sloping ground meant the undersized lift could not reach the upper right section of

the mural. By the time we reached the far end, the ground had dropped a full story.

We considered various options. A larger lift was suggested and quickly dismissed due to time constraints. Next, we tried painting

the head using extremely long extensions. First, we painted as high as possible from the lift. Then working from the top floor,

we took turns leaning over, blood rushing to our heads, reaching as far as we could from the top of the parking ramp. It felt as if

we were painting while preparing to perform a somersault five stories up, off the edge of the building. With guidance from the

ground and help from others, we eventually managed to paint the background.

However, it was extremely difficult, almost impossible, to paint a sharp line with a 10-foot extension. Our attempts to paint the

head with extension rollers was disastrous and completely unacceptable. Still, at least, we were able to paint the background

color. The attempt also gave us some idea of how high we could effectively paint details.

Hours passed; nothing was resolved. We were running out of time. I realized that, as an artist, Sachio wanted to stay true to the

original drawing, yet we all knew that was impossible. We were in a predicament. Sachio knew what had to be done but could

not bring himself to do it. I took the drawing from his hands and sketched a smaller head. I am no artist, and, worst of all, my

drawing was not based on aesthetics. It was solely based on what I thought we could reach. It lacked any artistic style, in part

because I had to attempt to blend it in with the portion we had already painted. Somewhat reluctantly and somewhat relieved,

Sachio agreed. Suddenly, I was the artist.

Even my smaller head turned out to be nearly impossible to paint. Extending the lift as far as possible, Tim, another assistant,

climbed higher, standing on a lower handrail so he could reach as high as possible. I remember holding on to Tim’s legs as he

painted the head. It was not nearly as sharp a line as the rest of the mural but, it was done. That evening our beer never tasted

so good. We were especially relieved that no one had died. For many years, whenever I drove past I would look up and think to

myself: “The head is too small”.

The beak that was supposed to peak near the top of the fourth floor now dropped to the middle of the third floor. I had turned a

depiction of a powerful soaring thunderbird into that of a weakened, nose-diving disproportionate caricature. Worst of all was

the beak. Rather than a magnificent powerful thunderbird, the mural now looked more like a canary.

Today the mural is gone. It was destroyed when the parking structure was replaced with a larger version. Gone, too, are most of

the other murals and even Sachio himself.

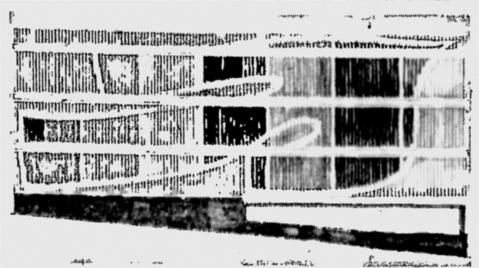

Major Fissure

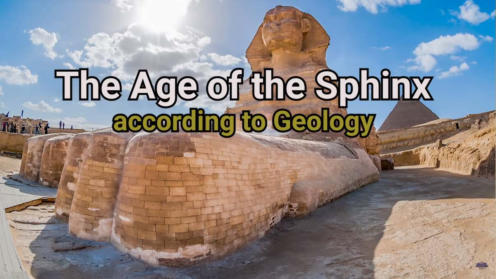

It turns out the builders of the Sphinx faced a similar problem. Carving from the top down, they uncovered a small cave as they worked. Hidden beneath the weather resistant Member III capstone, the cave lay undiscovered until workers reached the back of the Sphinx. The cave was formed over millions of years by acidic groundwater that had slowly dissolve the limestone. In places, this gave the limestone a Swiss cheese like appearance. Elsewhere, dissolution widened the bedrock fractures, in some places wide enough to create caves. I remember visiting a similar cave in a remote section of Canyonlands National Park in Utah years ago. The cave was wide enough to walk through, yet, at the surface above, it was a barely discernable crack. In the cave, I had to be careful while walking as the crack shrank to be slightly wider than my foot, but not wide enough to fall through. The fracture continued for some unknown distance downward past the cave floor. Almost exactly like at the Sphinx, acidic groundwater had slowly sculptured a cave, leaving the more resistant layers above and below relatively untouched. Prior to construction, there was no way for the Sphinx artist to know that the Major Fissure was any different from any of the other fractures that cross the ground. Then, like Sachio 4,500 years later, the artist faced a dilemma. The cave crossed the Sphinx body exactly where the rear paws should be. The Major Fissure divided the Sphinx into two parts. There was only one option: span the gap with limestone blocks and elongate the body. This allowed the rear paws to be carved in the higher quality Member I limestone. The result was the same as with Sachio’s thunderbird -- the head was now too small for the body. Hoping to stay true to the original plan, the artist, like Sachio, probably found it difficult to alter the drawing. I can’t help but wonder if it wasn’t the artist, but another volunteer, many years ago, who had the gumption to make the change. Monolith or Megalith The Sphinx is often referred to as a monolith. Monolith is an archaeological term used to describe prehistoric structures constructed from a single large block of stone. Examples include the ancient Egyptian obelisks and the T-pillars of Göbekli Tepe. Monolith is also a geologic term used to describe a single massive rock outcrop. Perhaps the best-known example is Uluru (Ayers Rock) in the Northern Territory of Australia. As the Sphinx limestone is broken by a series of bedrock fractures, it cannot be considered a monolith in a geologic sense. Using either the archaeological or geological definition the Sphinx is clearly not a monolith. Megalith Megalith is an archaeological term to describe prehistoric stone structures or monuments constructed using multiple large stones. An example would be the ancient Egyptian pyramids. Since large limestone blocks filled the Major Fissure gap, it seems the Sphinx would appear to be a megalith. Monolith Yet archaeologists, even those who know blocks were used to fill the Major Fissure, continue to refer to the Sphinx as a monolith. The confusion comes from archaeology. Their definition of a monolith includes any stone structure or monument that contains at least one massive stone, even if smaller stones were also used. Using that definition, archaeologists consider the Sphinx a monolith, even though the Sphinx itself was not carved from a single piece of bedrock as is commonly assumed.Battle of the Geologists

The Great Sphinx, which sits in front of the three great pyramids on the Giza Plateau in Egypt, has been the subject of controversy with regard to its age. Geologist Robert Schoch claims that it is thousands of years older than Egyptologists say and that it is the product of a lost civilization. Other experts in geology have weighed in on the subject too. What do they think about the geological evidence and the origins of the Sphinx? Dr. Miano at the World of Antiquity tackles this question in this video.Next Newsletter

The Lay of the Land

The Giza Pyramid Complex including the Great Sphinx are said to be part of a plateau. Plateaus are large areas of high flat lying terrain with cliffs on all sides. At Giza, the land slopes towards the South-East, in the direction of the Sphinx. The Sphinx itself sits just 20 meters (66 feet) above sea level and within the Nile River floodplain, certainly not what anyone could consider an elevated terrain. If not a plateau, then what is it? In the next newsletter I use geology to determine what the area looked like prior to construction of the Giza Pyramid Complex, and what it is called. If your have not already registered for the newsletter, click here to receive an email version as soon as it is released.

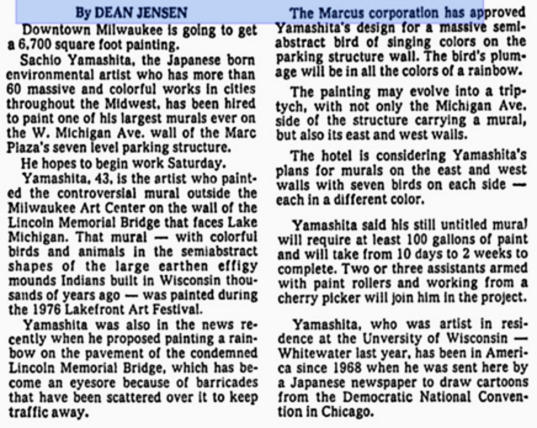

Milwaukee Sentinel Friday August 13, 1976

Sachio’s original drawing of the thunderbird mural.

Photo of the Major Fissure prior to repairs in the 1920s.

The Sphinx

Head is too Small

Mysteries of the

Great Sphinx

Wormhole Cave, Canyonlands National Park

I visited this cave prior to the area being closed for scientific study. Even then I

never enter the “arena” itself to protect the integrity of the scientific research.

© Robert Adam Schneiker 2023

RobertSchneiker.com

The Sphinx head is too small for the body. That fact

is obvious to anyone who sees the enormous

artwork. It just does not look right. The proportions

are wrong. One can only stare and wonder “What

was the artist thinking?”

In August 1976 I was part of a team painting a mural

on the Marc Plaza hotel parking structure in

downtown Milwaukee. Nearly a block long and over

four stories tall, this artwork approaches the scale

of the Sphinx in Egypt. I was a hired hand working

for food and beer. The artist was Sachio Yamashita

from Japan. He told me he came to the United

States as a reporter to cover the 1968 Democratic

Convention in Chicago, Illinois. Then, like now, the

United States was a divided country. Senator Robert

F. Kennedy, the presumptive Democratic candidate

had been assassinated two months prior in June, as

had Martin Luther King Jr. that April. Meanwhile,

outside the convention hall protests to end the war

in Vietnam turned violent. As an outsider, Sachio had

difficulty understanding what was going on.

In addition to being a political reporter and artist,

Sachio was a restaurant reporter and a beer

connoisseur. As a foodie, he felt he could not really

understand the people of the United States until he

tasted their beer. Everyone told him the beer comes

from Milwaukee, so he headed north. He believed he

was about to visit one of the coolest places on

Earth: a city named the Milky Way as in the galaxy,

that also brews beer! The misunderstanding was

Sachio’s own doing as he had mistakenly translated

Milwaukee to Japanese as “Milky Way”. Perhaps it

had something to do with Wisconsin being the Dairy

State.

It was in Wisconsin that Sachio learned about Native

American effigy mounds. Wisconsin has the highest

concentration of effigy mounds anywhere in the

world. Between about 600–1100 CE, some

15,000–20,000 effigy mounds were constructed in

Southern Wisconsin. Effigy mounds were constructed

in the form of animals and ancestral spirit beings of

importance to the Native Americans. It is thought

the mounds principally functioned as spiritual or

religious sites, although some have served as burial

sites.

It was in Wisconsin that the Mound Builders, as they

are known, built the only intaglios to be found

anywhere in the World. Intaglios are depressions in

the ground sculptured in the shape of animals and

spirits, making them the exact opposite of an effigy

mound. The only known remaining intaglio is in Fort

Atkinson, Wisconsin. Occasionally after a heavy

downpour the depression fills with water, bringing

the water spirit to life.

The Mound Builders mark the transition from hunter-

gatherers to agriculture. Although maize had long

been cultivated in Central and South America,

farming did not reach the Upper Midwest until much

later. Perhaps not surprisingly, the switch to

agriculture roughly coincides with a global warming

event known as the Medieval Warm Period from

900–1300 CE. You can learn more about the effigy

mounds and intaglios at this presentation by Robert

Birmingham a former Wisconsin state archaeologist.

The mural we were painting was Sachio’s

interpretation of a thunderbird effigy mound

modified to fit the proportions of the parking

structure. To Native Americans, thunderbirds are

symbols of great power and strength. They offer

protection from evil spirits. Perhaps I am biased, but

I see the influence of effigy mounds in much of

Sachio’s work, including perhaps his most famous

mural “Balance of Power” in Chicago. It can be seen

briefly in the famous car chase in the Blues Brothers

movie. A brief profile of Sachio and his work can be

seen in this episode of Chicago Tonight.

Sachio worked from a drawing to create the mural.

The drawing had to account for the horizontal

parking floors and vertical slats. The background was

painted a solid color, while the thunderbird itself

was colored with Sachio’s signature rainbow stripe

motif. A bringing together of the old and the new.

The drawing served a dual purpose. Sachio used the

drawing to sell the project to the hotel

management. This gave the decision makers an

opportunity to see what the finished mural would

look like. Next using the lift Sachio transferred the

drawing to the parking structure, using the vertical

slats and parking floors as a guide.

I was one of four volunteers. In groups of two, we

took turns painting. One person used a paint roller

while the other operated the lift. Sachio directed

the activities from below. I once saved the day by

repairing a leak in the lift hydraulic line. We were on

a tight schedule and did not have time to wait for a

mechanic from the lift rental company to make the

repair. Besides, I saw it was an easy fix using the

available tools.

Soon the work became routine. We would paint all

day, stopping for a quick lunch. At night we dined on

hotel food served from one of the finest restaurants

in Milwaukee, drinking imported German beer at the

hotel bar until late into the night. All costs were

covered by the hotel. We returned the next morning

to repeat the process.

With perfect summer weather, we were ahead of

schedule as we began our final day of painting.

Working from left to right and bottom up, we have

painted everything but the head. Sachio joined me

in the bucket to outline the final section. Using the

lift controls, I raised us, but we stop short. I tried

repositioning the lift, yet still we could not reach

high enough to draw the head. I got a sinking

feeling, as I wonder if my repair was to blame. No, it

turned out the lift was just too small.

Sachio had measured the height of the parking

structure. His measurements were used to

determine how large a lift was required to paint the

mural. Unfortunately, he had forgotten to account

for the slope of the land.

Working from left to right no one realize the sloping

ground meant the undersized lift could not reach the

upper right section of the mural. By the time we

reached the far end, the ground had dropped a full

story.

We considered various options. A larger lift was

suggested and quickly dismissed due to time

constraints. Next, we tried painting the head using

extremely long extensions. First, we painted as high

as possible from the lift. Then working from the top

floor, we took turns leaning over, blood rushing to

our heads, reaching as far as we could from the top

of the parking ramp. It felt as if we were painting

while preparing to perform a somersault five stories

up, off the edge of the building. With guidance from

the ground and help from others, we eventually

managed to paint the background.

However, it was extremely difficult, almost

impossible, to paint a sharp line with a 10-foot

extension. Our attempts to paint the head with

extension rollers was disastrous and completely

unacceptable. Still, at least, we were able to paint

the background color. The attempt also gave us

some idea of how high we could effectively paint

details.

Hours passed; nothing was resolved. We were

running out of time. I realized that, as an artist,

Sachio wanted to stay true to the original drawing,

yet we all knew that was impossible. We were in a

predicament. Sachio knew what had to be done but

could not bring himself to do it. I took the drawing

from his hands and sketched a smaller head. I am no

artist, and, worst of all, my drawing was not based

on aesthetics. It was solely based on what I thought

we could reach. It lacked any artistic style, in part

because I had to attempt to blend it in with the

portion we had already painted. Somewhat

reluctantly and somewhat relieved, Sachio agreed.

Suddenly, I was the artist.

Even my smaller head turned out to be nearly

impossible to paint. Extending the lift as far as

possible, Tim, another assistant, climbed higher,

standing on a lower handrail so he could reach as

high as possible. I remember holding on to Tim’s legs

as he painted the head. It was not nearly as sharp a

line as the rest of the mural but, it was done. That

evening our beer never tasted so good. We were

especially relieved that no one had died. For many

years, whenever I drove past I would look up and

think to myself: “The head is too small”.

The beak that was supposed to peak near the top of

the fourth floor now dropped to the middle of the

third floor. I had turned a depiction of a powerful

soaring thunderbird into that of a weakened, nose-

diving disproportionate caricature. Worst of all was

the beak. Rather than a magnificent powerful

thunderbird, the mural now looked more like a

canary.

Today the mural is gone. It was destroyed when the

parking structure was replaced with a larger version.

Gone, too, are most of the other murals and even

Sachio himself.

Major Fissure

It turns out the builders of the Sphinx faced a similar problem. Carving from the top down, they uncovered a small cave as they worked. Hidden beneath the weather resistant Member III capstone, the cave lay undiscovered until workers reached the back of the Sphinx. The cave was formed over millions of years by acidic groundwater that had slowly dissolve the limestone. In places, this gave the limestone a Swiss cheese like appearance. Elsewhere, dissolution widened the bedrock fractures, in some places wide enough to create caves. I remember visiting a similar cave in a remote section of Canyonlands National Park in Utah years ago. The cave was wide enough to walk through, yet, at the surface above, it was a barely discernable crack. In the cave, I had to be careful while walking as the crack shrank to be slightly wider than my foot, but not wide enough to fall through. The fracture continued for some unknown distance downward past the cave floor. Almost exactly like at the Sphinx, acidic groundwater had slowly sculptured a cave, leaving the more resistant layers above and below relatively untouched. Prior to construction, there was no way for the Sphinx artist to know that the Major Fissure was any different from any of the other fractures that cross the ground. Then, like Sachio 4,500 years later, the artist faced a dilemma. The cave crossed the Sphinx body exactly where the rear paws should be. The Major Fissure divided the Sphinx into two parts. There was only one option: span the gap with limestone blocks and elongate the body. This allowed the rear paws to be carved in the higher quality Member I limestone. The result was the same as with Sachio’s thunderbird -- the head was now too small for the body. Hoping to stay true to the original plan, the artist, like Sachio, probably found it difficult to alter the drawing. I can’t help but wonder if it wasn’t the artist, but another volunteer, many years ago, who had the gumption to make the change. Monolith or Megalith The Sphinx is often referred to as a monolith. Monolith is an archaeological term used to describe prehistoric structures constructed from a single large block of stone. Examples include the ancient Egyptian obelisks and the T-pillars of Göbekli Tepe. Monolith is also a geologic term used to describe a single massive rock outcrop. Perhaps the best-known example is Uluru (Ayers Rock) in the Northern Territory of Australia. As the Sphinx limestone is broken by a series of bedrock fractures, it cannot be considered a monolith in a geologic sense. Using either the archaeological or geological definition the Sphinx is clearly not a monolith. Megalith Megalith is an archaeological term to describe prehistoric stone structures or monuments constructed using multiple large stones. An example would be the ancient Egyptian pyramids. Since large limestone blocks filled the Major Fissure gap, it seems the Sphinx would appear to be a megalith. Monolith Yet archaeologists, even those who know blocks were used to fill the Major Fissure, continue to refer to the Sphinx as a monolith. The confusion comes from archaeology. Their definition of a monolith includes any stone structure or monument that contains at least one massive stone, even if smaller stones were also used. Using that definition, archaeologists consider the Sphinx a monolith, even though the Sphinx itself was not carved from a single piece of bedrock as is commonly assumed.Battle of the Geologists

The Great Sphinx, which sits in front of the three great pyramids on the Giza Plateau in Egypt, has been the subject of controversy with regard to its age. Geologist Robert Schoch claims that it is thousands of years older than Egyptologists say and that it is the product of a lost civilization. Other experts in geology have weighed in on the subject too. What do they think about the geological evidence and the origins of the Sphinx? Dr. Miano at the World of Antiquity tackles this question in this video.Next Newsletter

The Lay of the Land

The Giza Pyramid Complex including the Great Sphinx are said to be part of a plateau. Plateaus are large areas of high flat lying terrain with cliffs on all sides. At Giza, the land slopes towards the South- East, in the direction of the Sphinx. The Sphinx itself sits just 20 meters (66 feet) above sea level and within the Nile River floodplain, certainly not what anyone could consider an elevated terrain. If not a plateau, then what is it? In the next newsletter I use geology to determine what the area looked like prior to construction of the Giza Pyramid Complex, and what it is called. If your have not already registered for the newsletter, click here to receive an email version as soon as it is released.

Milwaukee Sentinel Friday August 13, 1976

Sachio’s original drawing of the thunderbird mural.

The Sphinx Head is too Small

Mysteries of the

Great Sphinx

Photo of the Major Fissure prior to repairs in the 1920s.

Wormhole Cave, Canyonlands National Park

I visited this cave prior to the area being closed for scientific study.

Even then I never enter the “arena” itself to protect the integrity of

the scientific research.