RobertSchneiker.com

The world’s first scientific instrument used by the ancient Egyptians to forecast the future

The morning view from my hotel roof-top deck is amazing. The Great Pyramid of Khufu is directly to the west; south of it is the Pyramid of Khafre, with the Pyramid of Menkaure again slightly farther south. The limestone bedrock lies naked, devoid of vegetation, in the unrelenting desert sun. Following the bedding plane, the Giza cuesta slopes gently toward the southeast in the direction of the Sphinx, forming a natural ramp that was used to construct the pyramids. Although just two blocks away, the Sphinx itself cannot be seen; my view is blocked by several buildings. Turning around looking east I see the sun rising over a seemingly endless city. Not long ago all of this would have been farmland. A block away, chaotic traffic on the congested Mansoureya Canal Street is at a near standstill. Traffic laws seem nonexistent. Still there are few, if any, accidents as drivers use their horns like Morse code to communicate as they make their way. Soon I will be a part of that chaotic scene as I wait for my driver to take me to the Cairo Museum. As I am absorbed in such thoughts, the city noise is suddenly rocked by a massive explosion! Startled, I look around to see a plume of smoke rising into a clear blue sky near the Sphinx. Like everyone, I was concerned about safety while traveling in Egypt. I had been warned beforehand about this by the hotel owner upon my arrival in Cairo. “There could be protests!” he said. Two days earlier on my first morning in Cairo, while walking toward the Sphinx, my way was blocked by armored military style vehicles. I saw what looked like SWAT team police dressed in black carrying machine guns. They showed little interest in me. Passing, we exchanged quick glances as I made my way toward the Giza entrance ticket booth. Across the street, near the Pizza Hut, a few people were congregated. At first, I thought they were tourists. Soon I realized they were protestors. Unknown to me, just minutes prior to my arrival the protest had turned violent as protesters scuffled with the police. The police arrested 24 people and used tear gas to disperse the crowd. The explosion two days later was not a terrorist attack, it was a controlled detonation to demolish a building. Like many Egyptians the protestors earn their livelihood from tourism. Anxious to accommodate the tourists, locals have built their stores, hotels, and restaurants ever closer to the Sphinx. To most people the buildings are also their homes. Unfortunately, these are illegal structures built with little regard for safety or building codes. They are accidents waiting to happen. To protect both the tourists and owners, some of the buildings are to be demolished. The police are there to ensure the demolition work proceeds smoothly and without interruption. Such is life in the Anthropocene – a poignant reminder for the reason of my visit. For it is rising groundwater associated with city development that brought me to Egypt and the Sphinx in the first place. Every morning, as I have breakfast, the view gets better. I wonder if perhaps if I stay long enough, that the Sphinx itself can eventually be seen from my hotel rooftop. Soon the driver arrives, and I am off to see the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in downtown Cairo. I am dropped off in Tahrir Square, the epicenter of the Arab Spring protests in Egypt in 2011. The museum lives up to its reputation as a world class museum with its unrivalled collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts. It is an amazing experience. Laid out in a roughly chronological fashion, the exhibits are a journey through time. It is an enjoyable way to spend a day, although I had the feeling of missing out on equally interesting destinations elsewhere. My personal favorite was the Tutankhamun exhibit. Still, as with any museum visit, it does not take long until I’m overwhelmed.The Nilometer

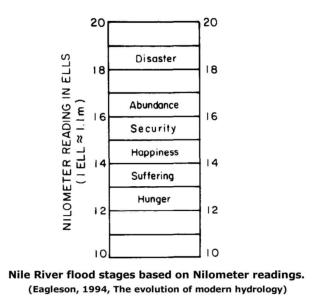

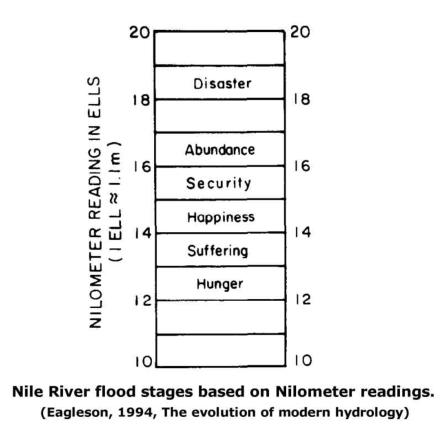

On the return trip to the hotel, I have added a stop. It is a place I have wanted to visit ever since I first heard of it. We head south from the museum, then east over a bridge to Rhoda Island, then south again. The street narrows until there is barely enough room for our car to pass. It becomes clear our driver has never been here before and is lost. He calls the hotel owner to receive updated directions. I am handed the phone and am assured we are almost there. Soon we stop in a small courtyard. A security guard points as he speaks with our driver. Getting out of the car, we see a man standing near what appears to be a small mosque. We tip the man, as with the security guard earlier. He unlocks the door, and we enter a dimly lit space. Surprisingly, although I am 9 km (5.6 miles) east of the Sphinx on an island in the Nile River, what is inside has much to say about the construction, history, and preservation of the Sphinx. What is even more remarkable is that what I am about to see marks the beginning of science: what some consider to be the greatest human achievement ever. For it is science that changed the way we view the world. Once inside, the sensation of a mosque grows stronger as I look up to see a grand dome. In front of me is a railing. I approach to see a staircase on the opposite side descending into darkness. It is difficult to see as my eyes take time to adjust to the lighting. Slowly I make out a square spiral staircase, reminiscent of an Escher drawing. It is exactly as I pictured it. Then as my eyes continue to adjust, I realize the hole is much deeper than I had imagined. In the center is an octagonal shaped limestone column covered with a series of evenly spaced horizontal lines. I am looking at the Nilometer, the world’s first scientific instrument. The importance of the Nile River to ancient Egypt cannot be overstated. If not for the Nile, Egypt would be a difficult, if not impossible, place to live. It was the annual flooding and associated silt deposition that allowed their civilization to flourish. This primitive instrument, and others like it, were used to measure the elevation of the Nile. By measuring the ebb and flow of the Nile, the ancient Egyptians were able to predict the maximum flood level. Its predictive power comes from comparing measurements taken on the same date over many years. The genius of the Nilometer lay in the realization that the past is the key to the future. Someone 5,000 years ago realized that by comparing daily water levels with previous years they could predict the height of the annual flood. That idea was both simple and radical. Somebody had to recognize that the world is knowable. It is a testament to the inventor’s foresight. The Nilometer demonstrates the core principle of science, that through careful observation the world is knowable, that it follows fixed laws, that it is not magic. At first, the measurements had little significance as there were no past measurements to use for comparison. As time went on the predictions became more accurate. Even though the Nilometer is based on ancient technology, similar stream gauges are still in use today. If not for the Aswan Dam, the Nilometer itself would likely still be used. Pharaohs would impress people with their ability to predict the floods. To the ancient Egyptians the ability to predict the future seemed like magic. Here was proof their pharaoh was indeed a god. Who else but a god could control the Nile? I imagine Pharaohs calling the people out for not living up to expectations if hunger or disaster was imminent… only to praise them for obedience when happiness and abundance were evident. Priests used the projections to estimate harvests and in turn taxes. For me this is one of the highlights of my trip to Egypt. I feel honored to be able to see the place where science began. We may never know the identity of the person who had the insight to begin this process. Nor will we ever know the names of the hundreds of people who took the readings over thousands of years. I find it difficult to believe this is one of the least popular archaeological sites in Egypt. It should be seen as a shrine to one of the greatest and most influential scientists who ever lived. The data was collected to predict the future; it now reveals the past. The Nilometer is part of the longest and oldest data set on Earth. The water level data constitutes the longest record of direct measurements anywhere in the world. The measurements are an accurate unbiased account of something that happened long ago. Hidden within the data are long term trends. For instance, using Nilometer data, climatologists discovered that El Ninos were far more common in the past, than they are today.Sphinx Island

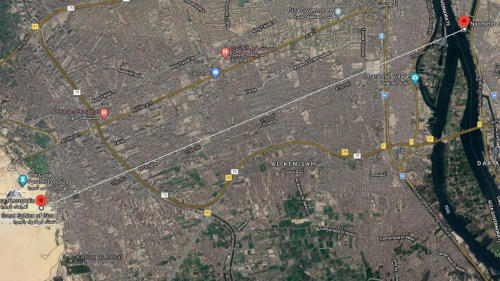

The Nilometer is almost directly side gradient to the Sphinx. This means that water level measurements taken at the Nilometer would be nearly identical to water levels at the Sphinx. The floor of the Sphinx enclosure sits at exactly 20 m (65.6 feet) above sea level. The Nilometer data reveals that on several occasions since AD 1430 the Sphinx Enclosure was inundated by the Nile flood waters, with floods reaching a maximum recorded height of 21.4 m (70.2 feet) above sea level -- making the Sphinx an island surrounded by 1.4 m (4.6 feet) of water. Based on my vadose zone modeling, the Nile would not actually need to flood the enclosure to erode the Sphinx. The Nilometer data indicates that on average over the past 1,400 years the water table was 2.4 m (7.9 feet) beneath the Sphinx enclosure floor: shallow enough for groundwater to wick up and evaporate in the hot desert sun. As the groundwater evaporates, salt accumulates in the rock pores. Pressure builds as salt crystals form, causing the limestone to flake off. Every year the annual floods recharged the groundwater beneath the Sphinx, ensuring the erosion process would continue. Luckily, the Sphinx has spent most of the past 4,500 years buried in windblown sand. Unable to wick up in the relatively coarse grain sand, erosion was turned off. Limestone quarried from the Sphinx Enclosure was used to construct the Sphinx Temple. The floor of the Sphinx Temple sits slightly lower than the Sphinx, at an elevation of 16.8 m (55.1 feet) above sea level. Using the Nilometer, we know the average maximum water level between AD 655–1899 is 17.6 m (57.7 feet) above sea level. This means, on average, over the past 1,400 years the Sphinx Temple was flooded with 0.8 m (2.6 feet) of water. The Nile River at the Nilometer has an annual average level of 15.4 m (50.5 feet) above sea level. The annual Nile River floods would last for months. Prior to completion of the Aswan Dan in 1970, flooding would begin in late July and not end until early January. This raises the obvious question: why would anyone build a temple that is flooded for part of the year? The answer is they did not. Enter the Palermo Stone (Royal Annals) which is considered one of the most significant written accounts of ancient Egypt ever discovered. It provides an account of the earliest Egyptian Pharaohs, including a few mythical ones from prior to the dynastic era. It is the cornerstone on which the history of the Old Kingdom is established. Among other things, the Palermo Stone includes Nilometer measurements from about 5100–4490 years ago indicating that the Sphinx and Sphinx Temple were constructed during a period of less flooding. Maximum flood levels fell by about 1 m (3.3 ft) from the 1st to the 4th dynasties, providing further evidence that the Sphinx and Sphinx Temple were built 4,500 years ago. That night back at the hotel, while drinking a beer, I can see and hear the “Pyramid Sound and Light Show”. I notice that a few more of the buildings are gone, but still the Sphinx itself cannot be seen. As I watch, I have time to ponder a mystery. The water table in the vicinity of the Sphinx, including beneath my hotel has risen. As you would expect, this has increased erosion of the Sphinx. A dewatering system has been installed lowering the water table protecting the Sphinx. But the source of so much water in a desert remains elusive. Look for the answer to that mystery in a future newsletter.What They Don’t Want You to Know

Ancient DNA preserved in soil may rewrite what we thought about the Ice Age No bones about it, mammoths appear to have survived the Younger Dryas. Fossil bone evidence indicates the last mammoths died some 12,000 years ago. New DNA evidence from soil samples suggests mammoths and other animals survived for a thousand years or more following their supposed extinction.Next Newsletter

The Sphinx: a monolith or megalith?

Most archaeologists believe the Sphinx is a monolith, carved entirely from the limestone bedrock. A few, like Zahi Hawass, believe the Sphinx is a megalith, that portions of the body were covered with limestone blocks quarried elsewhere. In the next newsletter I look at this controversial issue. If your have not already registered for the newsletter, click here to receive an email version as soon as it is released.

The Nilometer

Robert Schneiker at the Nilometer.

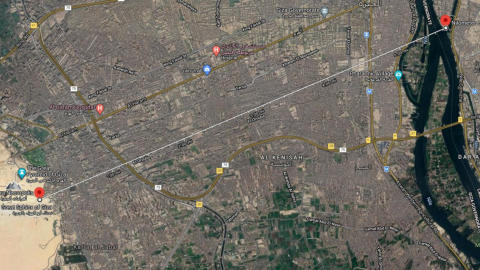

Location of the Nilometer in relation to the Sphinx.

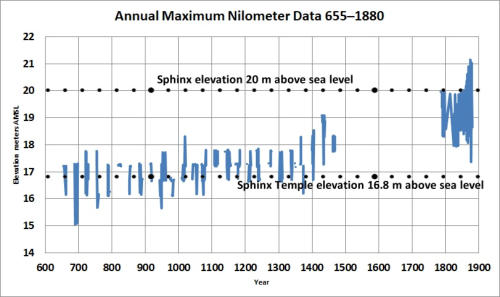

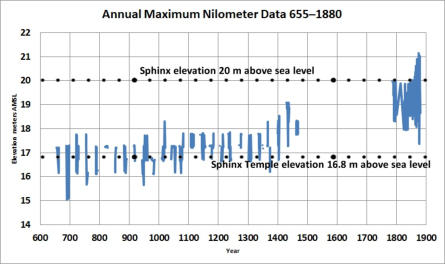

Annual Maximum Nilometer Water Elevations 655–1880.

Elevations above 20 m would flood the Sphinx Enclosure.

Elevations above 16.8 m would flood the Sphinx Temple.

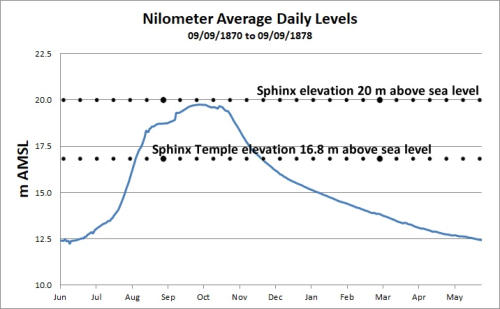

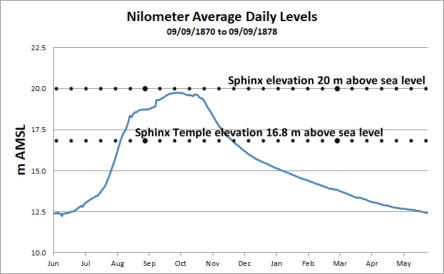

Nilometer Average Daily Elevations 1870–1878.

Elevations above 20 m would flood the Sphinx Enclosure.

Elevations above 16.8 m would flood the Sphinx Temple.

Mysteries of the

Great Sphinx

© Robert Adam Schneiker 2023

RobertSchneiker.com

The world’s first scientific instrument

used by the ancient Egyptians to

forecast the future

The morning view from my hotel roof-top deck is amazing. The Great Pyramid of Khufu is directly to the west; south of it is the Pyramid of Khafre, with the Pyramid of Menkaure again slightly farther south. The limestone bedrock lies naked, devoid of vegetation, in the unrelenting desert sun. Following the bedding plane, the Giza cuesta slopes gently toward the southeast in the direction of the Sphinx, forming a natural ramp that was used to construct the pyramids. Although just two blocks away, the Sphinx itself cannot be seen; my view is blocked by several buildings. Turning around looking east I see the sun rising over a seemingly endless city. Not long ago all of this would have been farmland. A block away, chaotic traffic on the congested Mansoureya Canal Street is at a near standstill. Traffic laws seem nonexistent. Still there are few, if any, accidents as drivers use their horns like Morse code to communicate as they make their way. Soon I will be a part of that chaotic scene as I wait for my driver to take me to the Cairo Museum. As I am absorbed in such thoughts, the city noise is suddenly rocked by a massive explosion! Startled, I look around to see a plume of smoke rising into a clear blue sky near the Sphinx. Like everyone, I was concerned about safety while traveling in Egypt. I had been warned beforehand about this by the hotel owner upon my arrival in Cairo. “There could be protests!” he said. Two days earlier on my first morning in Cairo, while walking toward the Sphinx, my way was blocked by armored military style vehicles. I saw what looked like SWAT team police dressed in black carrying machine guns. They showed little interest in me. Passing, we exchanged quick glances as I made my way toward the Giza entrance ticket booth. Across the street, near the Pizza Hut, a few people were congregated. At first, I thought they were tourists. Soon I realized they were protestors. Unknown to me, just minutes prior to my arrival the protest had turned violent as protesters scuffled with the police. The police arrested 24 people and used tear gas to disperse the crowd. The explosion two days later was not a terrorist attack, it was a controlled detonation to demolish a building. Like many Egyptians the protestors earn their livelihood from tourism. Anxious to accommodate the tourists, locals have built their stores, hotels, and restaurants ever closer to the Sphinx. To most people the buildings are also their homes. Unfortunately, these are illegal structures built with little regard for safety or building codes. They are accidents waiting to happen. To protect both the tourists and owners, some of the buildings are to be demolished. The police are there to ensure the demolition work proceeds smoothly and without interruption. Such is life in the Anthropocene – a poignant reminder for the reason of my visit. For it is rising groundwater associated with city development that brought me to Egypt and the Sphinx in the first place. Every morning, as I have breakfast, the view gets better. I wonder if perhaps if I stay long enough, that the Sphinx itself can eventually be seen from my hotel rooftop. Soon the driver arrives, and I am off to see the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in downtown Cairo. I am dropped off in Tahrir Square, the epicenter of the Arab Spring protests in Egypt in 2011. The museum lives up to its reputation as a world class museum with its unrivalled collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts. It is an amazing experience. Laid out in a roughly chronological fashion, the exhibits are a journey through time. It is an enjoyable way to spend a day, although I had the feeling of missing out on equally interesting destinations elsewhere. My personal favorite was the Tutankhamun exhibit. Still, as with any museum visit, it does not take long until I’m overwhelmed.The Nilometer

On the return trip to the hotel, I have added a stop. It is a place I have wanted to visit ever since I first heard of it. We head south from the museum, then east over a bridge to Rhoda Island, then south again. The street narrows until there is barely enough room for our car to pass. It becomes clear our driver has never been here before and is lost. He calls the hotel owner to receive updated directions. I am handed the phone and am assured we are almost there. Soon we stop in a small courtyard. A security guard points as he speaks with our driver. Getting out of the car, we see a man standing near what appears to be a small mosque. We tip the man, as with the security guard earlier. He unlocks the door, and we enter a dimly lit space. Surprisingly, although I am 9 km (5.6 miles) east of the Sphinx on an island in the Nile River, what is inside has much to say about the construction, history, and preservation of the Sphinx. What is even more remarkable is that what I am about to see marks the beginning of science: what some consider to be the greatest human achievement ever. For it is science that changed the way we view the world. Once inside, the sensation of a mosque grows stronger as I look up to see a grand dome. In front of me is a railing. I approach to see a staircase on the opposite side descending into darkness. It is difficult to see as my eyes take time to adjust to the lighting. Slowly I make out a square spiral staircase, reminiscent of an Escher drawing. It is exactly as I pictured it. Then as my eyes continue to adjust, I realize the hole is much deeper than I had imagined. In the center is an octagonal shaped limestone column covered with a series of evenly spaced horizontal lines. I am looking at the Nilometer, the world’s first scientific instrument. The importance of the Nile River to ancient Egypt cannot be overstated. If not for the Nile, Egypt would be a difficult, if not impossible, place to live. It was the annual flooding and associated silt deposition that allowed their civilization to flourish. This primitive instrument, and others like it, were used to measure the elevation of the Nile. By measuring the ebb and flow of the Nile, the ancient Egyptians were able to predict the maximum flood level. Its predictive power comes from comparing measurements taken on the same date over many years. The genius of the Nilometer lay in the realization that the past is the key to the future. Someone 5,000 years ago realized that by comparing daily water levels with previous years they could predict the height of the annual flood. That idea was both simple and radical. Somebody had to recognize that the world is knowable. It is a testament to the inventor’s foresight. The Nilometer demonstrates the core principle of science, that through careful observation the world is knowable, that it follows fixed laws, that it is not magic. At first, the measurements had little significance as there were no past measurements to use for comparison. As time went on the predictions became more accurate. Even though the Nilometer is based on ancient technology, similar stream gauges are still in use today. If not for the Aswan Dam, the Nilometer itself would likely still be used. Pharaohs would impress people with their ability to predict the floods. To the ancient Egyptians the ability to predict the future seemed like magic. Here was proof their pharaoh was indeed a god. Who else but a god could control the Nile? I imagine Pharaohs calling the people out for not living up to expectations if hunger or disaster was imminent… only to praise them for obedience when happiness and abundance were evident. Priests used the projections to estimate harvests and in turn taxes. For me this is one of the highlights of my trip to Egypt. I feel honored to be able to see the place where science began. We may never know the identity of the person who had the insight to begin this process. Nor will we ever know the names of the hundreds of people who took the readings over thousands of years. I find it difficult to believe this is one of the least popular archaeological sites in Egypt. It should be seen as a shrine to one of the greatest and most influential scientists who ever lived. The data was collected to predict the future; it now reveals the past. The Nilometer is part of the longest and oldest data set on Earth. The water level data constitutes the longest record of direct measurements anywhere in the world. The measurements are an accurate unbiased account of something that happened long ago. Hidden within the data are long term trends. For instance, using Nilometer data, climatologists discovered that El Ninos were far more common in the past, than they are today.Sphinx Island

The Nilometer is almost directly side gradient to the Sphinx. This means that water level measurements taken at the Nilometer would be nearly identical to water levels at the Sphinx. The floor of the Sphinx enclosure sits at exactly 20 m (65.6 feet) above sea level. The Nilometer data reveals that on several occasions since AD 1430 the Sphinx Enclosure was inundated by the Nile flood waters, with floods reaching a maximum recorded height of 21.4 m (70.2 feet) above sea level -- making the Sphinx an island surrounded by 1.4 m (4.6 feet) of water. Based on my vadose zone modeling, the Nile would not actually need to flood the enclosure to erode the Sphinx. The Nilometer data indicates that on average over the past 1,400 years the water table was 2.4 m (7.9 feet) beneath the Sphinx enclosure floor: shallow enough for groundwater to wick up and evaporate in the hot desert sun. As the groundwater evaporates, salt accumulates in the rock pores. Pressure builds as salt crystals form, causing the limestone to flake off. Every year the annual floods recharged the groundwater beneath the Sphinx, ensuring the erosion process would continue. Luckily, the Sphinx has spent most of the past 4,500 years buried in windblown sand. Unable to wick up in the relatively coarse grain sand, erosion was turned off. Limestone quarried from the Sphinx Enclosure was used to construct the Sphinx Temple. The floor of the Sphinx Temple sits slightly lower than the Sphinx, at an elevation of 16.8 m (55.1 feet) above sea level. Using the Nilometer, we know the average maximum water level between AD 655–1899 is 17.6 m (57.7 feet) above sea level. This means, on average, over the past 1,400 years the Sphinx Temple was flooded with 0.8 m (2.6 feet) of water. The Nile River at the Nilometer has an annual average level of 15.4 m (50.5 feet) above sea level. The annual Nile River floods would last for months. Prior to completion of the Aswan Dan in 1970, flooding would begin in late July and not end until early January. This raises the obvious question: why would anyone build a temple that is flooded for part of the year? The answer is they did not. Enter the Palermo Stone (Royal Annals) which is considered one of the most significant written accounts of ancient Egypt ever discovered. It provides an account of the earliest Egyptian Pharaohs, including a few mythical ones from prior to the dynastic era. It is the cornerstone on which the history of the Old Kingdom is established. Among other things, the Palermo Stone includes Nilometer measurements from about 5100–4490 years ago indicating that the Sphinx and Sphinx Temple were constructed during a period of less flooding. Maximum flood levels fell by about 1 m (3.3 ft) from the 1st to the 4th dynasties, providing further evidence that the Sphinx and Sphinx Temple were built 4,500 years ago. That night back at the hotel, while drinking a beer, I can see and hear the “Pyramid Sound and Light Show”. I notice that a few more of the buildings are gone, but still the Sphinx itself cannot be seen. As I watch, I have time to ponder a mystery. The water table in the vicinity of the Sphinx, including beneath my hotel has risen. As you would expect, this has increased erosion of the Sphinx. A dewatering system has been installed lowering the water table protecting the Sphinx. But the source of so much water in a desert remains elusive. Look for the answer to that mystery in a future newsletter.What They Don’t Want You to Know

Ancient DNA preserved in soil may rewrite what we thought about the Ice Age No bones about it, mammoths appear to have survived the Younger Dryas. Fossil bone evidence indicates the last mammoths died some 12,000 years ago. New DNA evidence from soil samples suggests mammoths and other animals survived for a thousand years or more following their supposed extinction.Next Newsletter

The Sphinx: a monolith or megalith?

Most archaeologists believe the Sphinx is a monolith, carved entirely from the limestone bedrock. A few, like Zahi Hawass, believe the Sphinx is a megalith, that portions of the body were covered with limestone blocks quarried elsewhere. In the next newsletter I look at this controversial issue. If your have not already registered for the newsletter, click here to receive an email version as soon as it is released.

The Nilometer

Nilometer Average Daily Elevations 1870–1878.

Elevations above 20 m would flood the Sphinx Enclosure.

Elevations above 16.8 m would flood the Sphinx Temple.

Annual Maximum Nilometer Water Elevations 655–1880.

Elevations above 20 m would flood the Sphinx Enclosure.

Elevations above 16.8 m would flood the Sphinx Temple.

Location of the Nilometer in relation to the Sphinx.

Robert Schneiker at the Nilometer.

Mysteries of the

Great Sphinx